What Is International Morse Code?

International Morse code is a telecommunications method used to send text characters through standardized sequences of signal durations made from dots, dashes, dits, and dahs. It follows global rules like Recommendation ITU-R M.1677-1 and Recommendation ITU-R M.1172, which define abbreviations, standard timing, and signal clarity so that trained users can understand messages clearly. The sound is usually a high pitched sound with a Pitch measured in Hz, commonly 550, and the Volume can be adjusted from 0 to 100. The speed is counted in words per minute, also called WPM, based on the PARIS standard word. Beginners often learn using Farnsworth speed, where space between letters and words is longer, making patterns easier to recognize. Each code symbol follows a sequence with a dit duration as the basic unit of time measurement, while a dah duration is three times longer, and signal absence creates a space, such as three dits between letters and seven dits between a word. With practice, these patterns become memorized through human senses like sound waves and visible light, and are directly interpreted by persons trained in the system.

The system was created by Samuel Morse and other developers as a telegraph code and an alphabet-based code, with major improvements by Alfred Vail, an engineer in commercial telegraphy across North America, and later refined by Friedrich Gerke in Europe, forming the ITU International Morse code. It includes 26 basic Latin letters from A to Z, an accented Latin letter like É, Indo-Arabic numerals from 0 to 9, limited punctuation, and tools for messaging such as procedural signals and prosigns, usable in upper case and lower case. Every encoded character is separated by physical spaces and time, forming unique pattern codes that can be encode and decode as a message. Signals are transmitted using on-off keying through an information-carrying medium like electric current, radio waves, or sound waves, where signals are present or absent, similar to natural languages. Today, Morse alphabets support transliteration through existing codes using a translator for Latin, Hebrew, Arabic, and Cyrillic alphabets, allowing users to play, flash, vibrate, save, share, link, and send messages to friends. From my own experience practicing CW Radio Tone with a modern beep sound on radio, and comparing it to the Telegraph Sounder with its original clicky noise, I’ve seen how American Morse differed in character speed, while modern Farnsworth speed and accented characters follow a simple form of encoding where numbers, symbols, and text are converted into lines of dot, dit, dash, and dah. These sound pulses, flashes, light, and physical taps once traveled through wires, aether, and telegraphs for decades, used in civilian and military settings, later discontinued for voice systems, yet still active in the 21st century as an easier and efficient communication system that does not transmit voice, but relies on patterns, wave, current, controlled opening and closing of a circuit, much like writing with short signal and long signal.

History of International Morse Code

In the nineteenth century, European experimenters explored electrical signaling systems using static electricity, Voltaic piles, and electrochemical changes as experimental designs and precursors to telegraphic applications. Hans Christian Ørsted in 1820 discovered the electromagnet, followed by William Sturgeon in 1824, who improved electromagnetic telegraphy in Europe and America. Early systems sent pulses of electric current through wires to control a receiving instrument, such as the single-needle system, a simple, robust instrument where a slow receiving operator used an alternate needle to write messages via deflection to the left or right, often with clicked, ivory, or metal stops. The Double Plate Sounder System by William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone in Britain, patented in June 1837 on the London and Birmingham Railway, marked the first commercial telegraph. Meanwhile, Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Eduard Weber in 1833, and Carl August von Steinheil in 1837, developed codes with varying word lengths, printed wheels, typefaces, and hammers. In America, Joseph Henry, a mechanical engineer, contributed to electrical telegraph systems, where on or off signals of electrical pulses represented natural language, laying the foundation for modern International Morse code. Operators relied on indentations on paper tape, with armatures and styluses to record transmissions, including numerals, letters, and special characters, efficiently encoding and decoding messages.

The American Morse code, also called Railroad Morse, spread quickly across U.S. telegraph networks. By 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse sent the first official message, “What hath God wrought”, from the Capitol in Washington, D.C., to Baltimore, demonstrating the revolutionary ability to exchange information over long distances. Modifications in Europe led to Continental Morse code by 1865, published by the International Telegraph Union, simplifying pauses, singular characters, and creating consistent spacing between signals. Later, Gerke’s revisions in Germany and Austria introduced new codepoints for letters like J, and revised digits 0–9, while retaining efficient, straightforward communication for telegraphists, trained to listen, transmit, and adopt these codes as almost a second language. Over decades, these changes resolved awkward and cumbersome patterns, standardized diacritics, and established the International Morse Code Recommendation ITU-R M.1677-1, ensuring consistency and usability even for experienced telegraphists in civilian and military contexts.

How International Morse Code Is Used in Real Life

From the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, International Morse Code began to be used extensively for early radio communication, when it was not yet possible to transmit voice. In the 1890s, high-speed international communication relied on telegraph lines, undersea cables, and radio circuits, because previous transmitters were bulky, and the spark gap system made transmission dangerous and difficult. By 1910, the U.S. Navy experimented with sending signals from an airplane, leading to the first regular aviation radiotelegraphy. Airships had enough space to accommodate large, heavy radio equipment, and in that year, America became instrumental in coordinating rescue of a crew. During World War I, Zeppelin airships were equipped for bombing and naval scouting, using ground-based radio direction finders for airship navigation. Allied airships and military aircraft relied on radiotelegraphy, since there was little aeronautical radio for general use in the 1920s. With no radio system, pilots on important flights like Charles Lindbergh’s New York to Paris journey in 1927 aboard the Spirit of St. Louis were truly incommunicado, completely alone in aviation history.

By the mid-1920s, regular use expanded, and in 1928, the airplane flight of the Southern Cross from California to Australia carried four crewmen, including a radio operator who communicated with ground stations using radio telegraph. From the Beginning of the 1930s, both civilian and military pilots were required to be able to use early communications systems for identification through navigational beacons. These beacons sent continuous two-letter identifiers or three-letter identifiers, which Aeronautical charts show next to each identifier as a navigational aid, helping pilots know the next location on a map. On land, rapidly moving field armies fought and moved quickly, so communications services had to be put up fast as new telegraph lines and telephone lines. This was seen especially during blitzkrieg offensives by the Nazi German Wehrmacht in Poland, Belgium, and France in 1940, later across the Soviet Union, North Africa, Italy, the Netherlands, southern Germany, and until 1945. Morse was vital for carrying messages between warships, naval bases, and all belligerents, enabling Long-range ship-to-ship communication with encrypted messages, since voice radio systems on ships were limited in range and security.

It was also used extensively by warplanes, long-range patrol planes, and navies to scout enemy warships, cargo ships, and troop ships. As the international standard for maritime distress, Morse remained critical until 1999, when it was replaced by the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System. The French Navy ceased Morse use on 31 January 1997, sending a final message transmitted as Calling all, last call, eternal silence. In the United States, the final commercial transmission occurred on 12 July 1999, signing off with the original 1844 message WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT, followed by the prosign SK, meaning end of contact. Even by 2015, the United States Air Force used Morse in trains and rescue exercises involving ten people, while the United States Coast Guard later ceased all use and no longer monitors radio frequencies or transmissions, including the international medium frequency (MF) distress frequency 500 kHz.

Despite this, the Federal Communications Commission still grants commercial radiotelegraph operator licenses, where applicants must pass code tests and written tests. Licensees even reactivated an old California coastal Morse station, KPH, which regularly transmit from the historic site using call sign KSM. Similarly, a few U.S. museum ship stations are operated by enthusiasts. In aviation, radio navigation aids allow pilots to ensure stations intend to remain serviceable, as each set of identification letters is usually a two-to-five-letter version of the station name. These Station identification letters are shown on air navigation charts, including VOR-DME stations based near places like Vilo Acuña Airport, Cayo Largo del Sur, Cuba, identified as UCL, repeatedly transmitted on a radio frequency. In some countries, during periods of maintenance, the facility sends TEST instead, or is removed, which tells navigators the aid is unreliable. In Canada, Morse may entirely signify a navigation aid is not to be used.

For amateur radio operators, Morse is today the most popular mode, commonly referred to as continuous wave (CW). Other faster keying methods are available, such as frequency-shift keying (FSK), but original Morse was used exclusively before voice-capable radio transmitters become commonly available around 1920. Until 2003, the International Telecommunication Union mandated proficiency as part of the amateur radio licensing procedure worldwide, but the World Radiocommunication Conference in 2003 made this requirement optional. Many countries later removed Morse requirements. In the United States, demonstration of the ability to send and receive at a minimum of five words per minute was once required for an amateur radio license. The Federal Communications Commission later reduced the Extra Class requirement from 20 WPM to 5 WPM, and finally, effective February 23, 2007, eliminated proficiency requirements for all amateur radio licenses.

Under U.S. rules, Morse is permitted on all amateur bands, including LF, MF low, MF high, HF, VHF, and UHF, with certain portions reserved for transmission of Morse signals only. These transmissions employ an on-off keyed radio signal, requires less complex equipment, and uses less bandwidth, typically 100–150 Hz wide. In contrast, voice communication needs about 2,400~2,800 Hz, such as SSB voice. Morse is usually received as a high-pitched audio tone, making it easier to copy in noise, congested frequencies, and very high noise environments. Because transmitted power is concentrated into a very limited bandwidth, it makes it possible to use narrow receiver filters to suppress or eliminate interference from nearby frequencies. This narrow signal bandwidth takes advantage of the natural aural selectivity of the human brain, further enhancing weak signal readability and efficiency. This is why Morse excels in DX long distance transmissions and low-power transmissions, commonly called QRP operation.

Because Morse has a relatively limited speed, it can be sent reliably and led to the development of an extensive number of abbreviations to speed communication, including prosigns and Q codes. A typical message might include CQ, a broadcast meaning “seek you,” OM (old man), YL (young lady), XYL (ex-young lady, meaning wife), and QTH, meaning transmitting location, often spoken as “my Q.T.H..” These terms permit conversation even when operators speak different languages. Over the years, Morse expanded into many fields, including the rail industry, where Rail companies started to report arrivals and departures, contributed to improving safety services. In Media, the invention had a direct impact on the advent of mass media, allowing news outlets to receive and communicate information instantly, such as Stock prices, weather reports, and important events, making the world shrink in a way that had not been possible until then.

In Maritime communication, Morse is still primarily associated with ships and the maritime industry. In the late 19th century, it became a universal language of the sea. For instance, when the Titanic struck an iceberg, it sent out two distress signals, first CQD, then SOS. In Emergency communication, if other systems fail, Morse would become one of the most efficient, reliable means when faced with an emergency. Sending the universal distress signal SOS in Morse code (…–––…) can let others know you need help. As a Hobby, amateur radio enthusiasts still enjoy Communicating with radio amateurs around the world, finding it enjoyable and rewarding, and nowadays it has become a kind of secret language. For history lovers, Morse offers a tangible connection to the past, a unique language from the 1800s that helped people communicate across land, encode secret tactics, and support wartime needs. In modern revival, Morse helps us gain perspective on how far communication has advanced.

Morse also remains active in Radio navigation aids like VORs, NDBs, and aeronautical use, where stations broadcast identifying information in Morse form, even though many VOR stations now also provide voice identification. Warships, including those of the U.S. Navy, have long used signal lamps to exchange messages while maintaining radio silence. The Automatic Transmitter Identification System (ATIS) uses Morse to identify uplink sources in analog satellite transmissions, and Many repeaters identify themselves even when voice communications are used. Another important application is signalling for help, which can be sent by keying on and off, flashing a mirror, toggling a flashlight, or similar methods. The signal SOS is not sent as three separate characters, but as a prosign, keyed without gaps, with a specific meaning. This start of a distress message tells all other transmissions to go silent for the duration.

Finally, Morse is employed in assistive technology, helping people with a variety of disabilities communicate. For example, the Android operating system (versions 5.0 and higher) allow users to input text using alternative methods such as keypad, handwriting recognition, or Morse, enabling persons with severe motion disabilities to send messages as long as they have some minimal motor control. In some cases, Morse acts as a speaking communication aid, using sip-and-puff interface devices or electronic typewriter systems. In intensive care units, cases have shown Morse used through blinking eyes, including the famous 1966 case of Jeremiah Denton, who Morse-blinked the word TORTURE on television, proving how powerful this system remains.

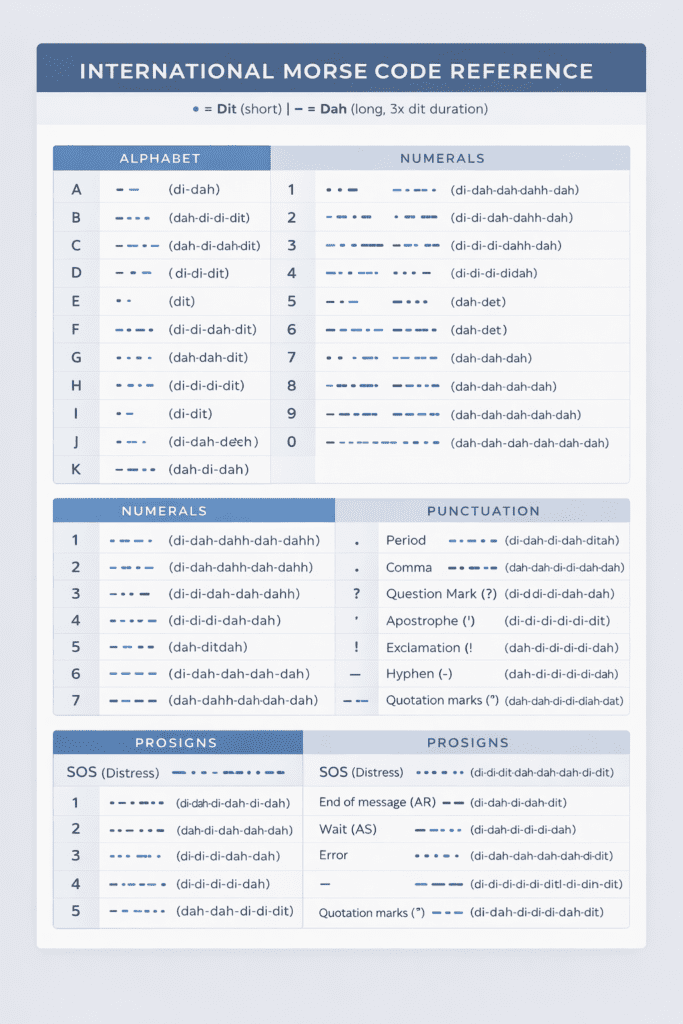

International Morse Code Reference Chart for Beginners

Timing and Speed in International Morse Code

In international morse code, timing is the heart of understanding sound, not dots on paper. Some methods of teaching focus on how people are learning and using rhythm instead of visuals, while others still use tools like the dichotomic search table. Morse is taught so learners can send and receive letters and other symbols, and their speed depends on full target speed, that is, sending with normal relative timing of dits, dahs, and spaces within each symbol, for that speed. One well-known approach is named after Donald R. Russ Farnsworth, also known by his call sign, W6TTB. However, initially, exaggerated spaces between symbols and words are used to give learners time, making the sound shape easier to learn. As spacing can then be reduced through practice and familiarity, I personally noticed my recognition improve faster once my ear stopped counting and started flowing.

Another popular teaching method, the Koch method, was invented in 1935 by a German engineer, former stormtrooper, Ludwig Koch, which uses full target speed from the outset. It begins with just two characters, and Once strings containing those two characters are copied at 90% accuracy, an additional character is added, and so on, until the full character set is mastered. In North America, many thousands of individuals increased code recognition speed after initial memorization of characters by listening to regularly scheduled code practice transmissions broadcast by W1AW station, American Radio Relay League’s headquarters, or listening to archived recordings available on its website. As of 2015, the United States military taught an 81 day self-paced course, having phased out more traditional classes. Visual mnemonic charts, devised over the ages, even by Baden-Powell, were included in one Girl Guides handbook in 1918. In the United Kingdom, many people learned by means of a series of words and phrases that have the same rhythm as a Morse character; For instance, Q, Morse, dah dah di dah, which was memorized as the phrase God Save the Queen, while F, di di dah dit, was memorized as Did she like it. This requires some dedication, but is an achievable task, and Here are a couple of tips to help you make the best possible progress mastering this skill: Take one character at a time, Use a table to learn the unique pattern of each character one by one—it doesn’t make sense to try and learn them all at once. Commit each character to your memory before you move on to the next one. Listen, immerse yourself; You will find online audio resources, They will guide you through the learning process, helping you distinguish between different signals and introduce patterns step-by-step. Take your time, you can find many other types of Morse code converters on the web that help you learn and practice—readers, charts, audio generators, and so on. Practice code regularly; Consistency is key. Try to dedicate some time each day, even if it’s just a few minutes of practice—the more you do, the more naturally it will come. Get in touch with other fans, Join online communities, forums, where everyone can share their tips and support each other. It’s also worth remembering that many radio enthusiasts use Morse to communicate, so that’s an opportunity you can enjoy too. In general, if you dedicate yourself to the task and keep at it, you’ll be reading like a pro in no time—it can be a truly rewarding and fun experience.

Technical Encoding and Transmission Logic

Transmission Methods can be transmitted a number of ways and I learned early on that sound is only one part of the system. Originally, electrical pulses moved along a telegraph wire, but were later extended into audio tone, radio signal, short tones, long tones, high tones, low tones, and even mechanical, audible, or visual signal, e.g., flashing light, using devices, like, Aldis lamp, heliograph, common flashlight, and even, car horn. Some mine rescues used pulling rope, short pull, dot, long pull, dah, while Ground forces send messages to aircraft with panel signalling, where, horizontal panel, dah, vertical panel, dit. messages are generally transmitted with a hand-operated device, such as, telegraph key, so, there are variations, introduced by skill, sender, receiver, and more experienced operators, can send, receive, faster speeds. In addition, individual operators, differ, slightly, example, using, slightly longer, shorter, dahs, gaps, perhaps, only, particular characters, This, called, their, fist; experienced operators can recognize, specific individuals, by, alone, and a good operator, who, sends, clearly, easy, copy, is said, have, good fist, while poor fist is characteristic, sloppy, hard, copy.

At the core, Binary Encoding is transmitted using just two states, on, off, and may be represented as binary code, that is what telegraph operators do, when transmitting messages. Working, from, above, ITU definition, further, defining, bit, as, dot time, a sequence may be crudely, represented as a combination of the following, five bit-strings: short mark, dot, dit, 1’b; longer mark, dash, dah, 111’b; intra-character gap, between, dits, dahs, within, character, 0; short gap, between letters, 000’b; medium gap, between words, 0000000’b. marks, gaps, alternate, Dits, always, separated, one, gaps, always, separated, dit, dah. A more efficient, binary encoding, uses, only, two-bits, for, each, dit, dah, element, with, 1 dit-length pause, must, follow, after, each, automatically, included, every, 2 bit code. One possible coding, by, number value, length, signal tone, sent, one, could, use, 01’b, for, automatic, single-dit pause, after, 11’b, automatic, single-dit following pause, 00’b, extra pause, between letters, in effect, end-of-letter mark, That, leaves, code, 10’b, available, some other purpose, such as, escape character, or, more compactly, represent, extra space, between words, end-of-word mark, instead, 00 00 00’b, only, 6 dit lengths, since, 7th, automatically inserted, as part, prior, dit, dah.

When dealing with Non-Latin Alphabets, a typical tactic is creating, codes, diacritics, as non-Latin alphabetic scripts have been, begin, simply, re-using, International Morse codes, already used, letters, whose, sound, matches, sound, local alphabet. Because, Gerke code, predecessor, International Morse, was, official use, central Europe, it included, four characters, not included, International Morse standard, Ä, Ö, Ü, CH, these four, served, beginning-point, other languages use, alphabetic script, but, require, codes, letters, not accommodated. The usual method, been, first, transliterate, sounds, represented, International code, four unique, Gerke codes, into, local alphabet, hence, Greek, Hebrew, Russian, Ukrainian, codes. If, more codes, needed, one, either, invent, new code, convert, otherwise, unused code, from, either, code set, non-Latin letter. For, Russian, Bulgarian, Russian Morse code, maps, Cyrillic characters, four-element codes, Many, those characters, encoded, same, their, Latin alphabet, look-alikes, sound-alikes, A, O, E, I, T, M, N, R, K, etc. The Bulgarian alphabet, contains, 30 characters, which, exactly, matches, number, all possible permutations, 1, 2, 3, 4, dits, dahs. Russian, Ы, used, as, Bulgarian, Ь; Russian, Ь, used, Bulgarian, Ъ; Russian, requires, two more codes, for, letters, Э, Ъ, which, each, encoded, with, 5 elements. Non-alphabetic scripts, require, more radical, adaption: Japanese Morse code, Wabun code, has, separate encoding, for, kana script, although, many, codes, used, for, International Morse, sounds, they, represent, mostly, unrelated, Japanese. Japanese, Wabun code, includes, special prosigns, for, switching, back-and-forth, from, International Morse. For, Chinese, Chinese telegraph code, used, map, Chinese characters, four-digit codes, send, these digits, out, using, standard Morse code. Korean Morse code, uses, SKATS mapping, originally, developed, allow, Korean, be typed, on, western typewriters, where SKATS, maps, hangul characters, arbitrary letters, Latin script, has, no relationship, pronunciation, Korean.

Modern Usage, Variations, and Special Characters of International Morse Code

Starting with Software and Modern Technology, I’ve personally seen how Although the traditional telegraph key, straight key, is still used by some amateurs, many now use mechanical semi-automatic keyers, informally called bugs, and fully automatic electronic keyers, called single paddle, either double-paddle, iambic keys, which are prevalent today. Software, also, frequently, employed, helps produce, decode, radio signals; the ARRL, has, a readability standard, where robot encoders, called ARRL Farnsworth spacing, are supposed to have higher readability, for both, robot, human decoders. Some programs, like, WinMorse, implemented this standard. Decoding software, ranges, from software-defined, wide-band radio receivers, coupled with the ReverseBeacon Network, which decodes signals, detects CQ messages, on ham bands, to smartphone applications. Variations, Encryption, also existed; During early World War I, 1914–1916, Germany, briefly, experimented, with dotty, dashy Morse, the essence being adding, dot, dash, end, each, symbol. Each one, was quickly, broken, by Allied SIGINT, standard Morse, resumed, Spring 1916, and Only, a small percentage, of Western Front, North Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea, traffic, was, dotty, dashy Morse, during, the entire war. In popular culture, it’s mostly, remembered, through the book, The Codebreakers, David Kahn, and national archives, UK, Australia, whose SIGINT operators, copied, most, this, variant. Other variations, include, forms, fractional Morse, fractionated Morse, which, recombine, characters, encoded message, then, encrypt, them, using, cipher, order, disguise, text.

Focusing on Special Characters, Prosigns Details, many symbols, !, $, &, are not defined, inside, the official ITU-R International Morse Code Recommendation, but, informal conventions, for them, exist. The @ symbol, was formally, added, in 2004; % symbol, ‰ symbols, both, have, recommended, long encodings. The Exclamation mark, There, is no standard representation, for the exclamation mark, !, although, the KW digraph, was proposed, in the 1980s, by Heathkit Company. While, translation software, prefers, the Heathkit version, on-air use, is not yet, universal, as, some amateur radio operators, North America, Caribbean, continue, use, older, MN digraph, copied, over, from, American Morse landline code. Currency symbols, the ITU, never, formally, codified, any, currency symbols, into, unambiguous, ISO 4217, currency codes, preferred, transmission, e.g., CNY, EUR, GBP, JPY, KRW, USD, etc. However, the symbol, $, is represented, in Phillips Code, as, two characters, SX, eventually, operators, dropped, the intervening space, merged, the two letter code, abbreviation, into, a single, unofficial, punctuation encoding, SX. The Ampersand, &, has a suggested, unofficial encoding; the ampersand, & sign, is often, shown, as AS, also, an official, prosign, wait. The Keyboard, at, sign, @, On, 24 May 2004, the 160th anniversary, of the first, public, telegraph transmission, the Radiocommunication Bureau, International Telecommunication Union, ITU-R, formally, added, the @ character, commercial at, commat, character, to the official, character set, using, the sequence, denoted, AC digraph. This sequence, reported, to have been, chosen, to represent, A[t], C[ommercial], or, the letter, a, inside, a swirl, represented, by the letter, C. This new character, facilitates, sending, e-mail addresses, and is notable, since, it, was the first, official addition, to the set, of characters, since, World War I. Percent, %, permille, ‰ signs, Percent, permille signs, should, be encoded, with, zeroes, separated, by a slash, joined, to the preceding, number, dash, so, e.g., 4%, would be sent, as, 4-0/0, 5‰, as, 5-0/00, 6.7%, as, 6.7-0/0.